By Sam Brunson

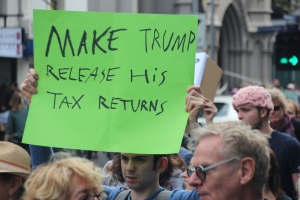

By now I’m sure you’ve read the New York Times story about the Trump gift tax evasion (or, if not that story—which is really, really long—at least a summary of it). There is a lot in there, and I suspect it’ll inspire more than a couple posts here, but I wanted to lead off with the statute of limitations.

Because let’s be real: I’ve always thought of the statute of limitations as being three years or, if you substantially understate your gross income, six years, unless you don’t file a return, in which case it runs forever until you file a return. Since most of the alleged fraud occurred in the 1990s or earlier, even the longer statute would be long passed.

It turns out that my mind entirely skipped over section 6501(c).[fn1] Section 6501(c) says that if you file a “false or fraudulent return,” there is no statute of limitations. The IRS can go in and assess a tax deficiency, with interest and penalties, whenever it wants.

Of course, the fact that the statute of limitations may not be closed yet doesn’t necessarily mean that the IRS is going to pursue Trump. He is, after all, the sitting president. And one major assertion the article made was that the IRS didn’t catch it the first time because the IRS was underfunded and understaffed; that hasn’t improved a ton.

Asserting fraud also places a significant burden on the IRS. Where the burden of proof is usually on the taxpayer to establish the correctness of her return, the IRS has the burden of proof where it asserts fraud and intent to evade tax. And proving fraud isn’t necessarily a light burden: the Tax Court has held that fraud requires the IRS to prove (a) the underpayment, and (b) “actual, intentional wrongdoing, … or the intentional commission of an act for the specific purpose of evading a tax believed to be owing” by the taxpayer.[fn2] And the IRS has to do so by clear and convincing evidence.

And there’s one further difficulty (represented by a circuit split): who committed the fraud? The Second Circuit has held that it doesn’t have to be the taxpayer (in this case, Fred Trump, who would have (or should have) filed gift tax returns and paid gift tax) who committed fraud. If the tax return preparer committed fraud, it’s still fraud, and there is no statute of limitations.[fn3] (And what if it was Donald who committed the fraud? I suspect that the Second Circuit could read its “return preparer” precedent to reach him, as long as he had a substantial part in preparing the returns.)

Presumably, it should be cut and dried, then. The Second Circuit governs New York, so its precedent, presumably, applies.

Only the split is with the Federal Circuit. And the Federal Circuit has nationwide jurisdiction. That is, if the IRS were to assert a deficiency, and Fred Trump’s estate were to pay that deficiency, it could sue either in a district court in New York or in the Court of Federal Claims. And appeals from the Court of Federal Claims lie in the Federal Circuit.

And what does the Federal Circuit say about fraudsters? That only the taxpayer’s fraud allows for no statute of limitations.[fn4] In other words, if the IRS were to assert fraud, it would also have to prove—by clear and convincing evidence—that the fraud was committed by Fred Trump, because unless it can prove that, his estate can choose to challenge the assertion under the Federal Circuit’s narrower standard.

[fn1] In my defense, I was sitting in my son’s capoeira class, reading the story on my phone, and evaluating things 100% on the basis of my memory.

[fn2] Price v. Comm’r, 71 T.C.M. (CCH) 2884 (T.C. 1996).

[fn3] City Wide Transit, Inc. v. Comm’r, 709 F.3d 102, 107 (2d Cir. 2013).

[fn4] BASR P’ship v. United States, 795 F.3d 1338, 1350 (Fed. Cir. 2015).

Good post on the law, but surely the chances of Fred Trump’s tax lawyers having committed criminal tax fraud are close to zero. And wouldn’t the returns have been routinely audited, too?

LikeLike

I have a question (I’ll ask Prof. Lederman if she’s at lunch with me tomorrow, but I think she’s out of town). The New York Times has tax returns obtained illegally, right? Can the Justice Dept. subpoena them in an investigation of who disclosed them? As I understand it, the NYT would not have liability for reporting the stolen information (unless, maybe, they paid for it or commissioned the theft). Am I right on that?

LikeLike

ps– Actually, could the NYT be liable on tortious interference with contract if it incentivized an IRS employee to breach his confidentiality agreement with the IRS?

LikeLike

Interesting questions. I don’t know the answers, but I can take a couple guesses. Regarding Fred Trump’s attorneys and accountants: I would hope they wouldn’t commit fraud, but it wasn’t unheard-of in the 1990s. But they wouldn’t have had to commit fraud for Trump to commit fraud: the attorneys would likely have relied on the valuations of the property that Fred Trump provided to them; if he provided fraudulent valuations, and they reasonably relied on those valuations (or whatever the standard was back then), there could have been fraud without Trump engaging in fraud.

And I’m pretty sure that you’re right that, even if the returns were obtained illegally, the Times wouldn’t have any legal liability. They don’t say how they got the documents—it could be from an IRS leaker (which would mean that the IRS leaker broke the law), but it could also be from the former employees they talked to, in which case, the tax law wouldn’t prohibit their disclosure (though there may be other legal or ethical bars to such disclosure).

Finally, it’s not at all clear that Trump would have been routinely audited. Maybe, but the IRS has been stretched thin for a long time. Moreover, even if the return were audited at the time, it’s not necessarily the case that the IRS would have pushed on valuation or transfer pricing issues; if they were well-hidden (or just generally opaque), they may not have come to the attention of the auditor.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Professor Brunson .

Another point on statutes of limitations, implicit in the original post: if a transaction was really a concealed gift, then no gift return would have been filed, so the statute of limitations is infinite. I still doubt there would be a criminal offense, but there wouldn’t have to be for the IRS to audit and to assess fines.

LikeLike

A criminal law point: if info is illegally obtained by a policeman, it can’t be used in court, but as I undrestand it (I may be wrong) if it is illegally obtained by a private citizen, it can. Thus, here, the info is not tainted even tho the NYTimes must have it illegally (whether from the IRS or from an accountant—tho, then, maybe it’s just grounds for damages and loss of license and I shouldn’t call it illegal).

LikeLike